An inventor caught up in the thrill of developing a new product, or an engineer trying to source parts from other companies to complete his new design, may understandably not have legal matters foremost in mind. But unless lady luck is on his side, leaving the issue of intellectual property to some later date when he is less preoccupied could prove very expensive indeed. The big players in the electronics and engineering markets owe their success to a number of different factors. Being in the right-place at the right time, focussing on their core strengths and products, their ability to adapt quickly to change (especially in core markets), and a heavy involvement in setting standards are just some of them. Although much of their success could be attributed to their CEOs and other senior staff, it could not have been achieved without the talent and ingenuity of their engineers and designers. But at least as importantly as any of these factors, all these companies recognised and appreciated, right from the start, the value in continually creating core intangible assets that would be needed by them, their competitors and others. They saw intellectual property as an asset. Yet even large organisations do not always pay the continual attention to maximising their intangible assets that they should, and many one-person start-ups ignore it completely. It is vital that everyone involved in the company, from the CEO to the engineers, understands the value in protecting and commercializing the intellectual assets. So what do we mean by the terms intellectual property, intellectual assets and intellectual capital? Most people assume that protecting their intellectual property means filing applications for patents or registering a trade mark, and that is certainly part of it. But the term intangible assets means far more than that. The various elements which make up an organisation's intangible assets are shown below.

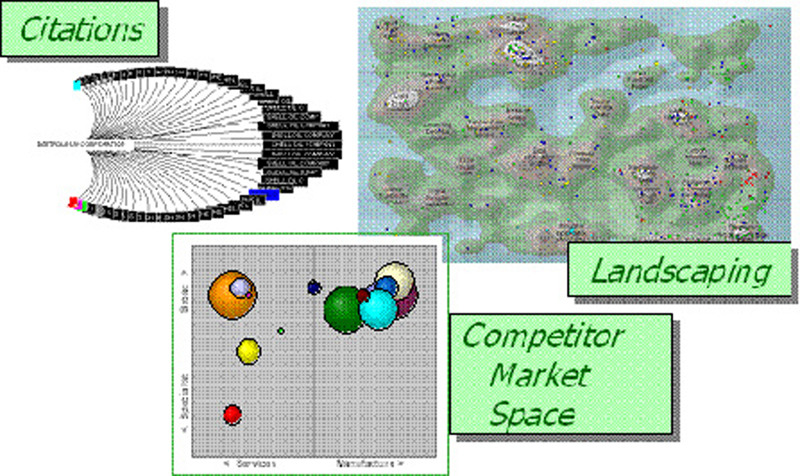

Intangible assets do not consist just of patents and other formal intellectual property rights (formal IP) such as trademarks, designs and copyright - which are underpinned by various statutes and laws. Formal IP is only a piece of the intangible assets jigsaw. Intangible assets also include customer and business relationships, workforce skills, branding, business processes, reputation and the know-how of employees, including electronic engineers and designers. Ideas and inventions provide a company's heart beat, while the wider intellectual capital drives growth and future revenues. Many small companies in the electronics industries have talented and inventive engineers yet the companies for whom they work fail - for a number of reasons - not only to protect, but also to commercialise, their designs and inventions which means they are not as successful as they could be. As a CEO or engineer in a start-up, you might think you are too small or specialised to be considered a threat by any of the giants with established IP. However, you should not forget that once the core product or process is marketed, unless IP protection is in place others may copy it, change it slightly and claim it as their own, leaving you behind with possibly potentially serious business consequences. The risk of your core product, process or idea being stolen, or that your company is not the first mover you thought it was, can be minimised by understanding where you, as a CEO or engineer, can contribute to the intangible assets jigsaw and where the core products you are working on lie within the IP matrix. A question you should ask is; are you and those in your company willing to recognise and appreciate, ideally from the very beginning or as soon as possible, the value in continually creating core intangible assets that would be needed by you, your competitors and others? At the very least, CEOs and engineers in the electronics industry need to be aware of what patents their competitors hold and how these may affect core products. You also need to be aware of the key elements of your core products. In this industry core products can range from a single component (e.g. A display, or chip), or several components working in unison to an entire product. And any of the components that make up your core product may be patentable or already patented by your competitors or suppliers which can be a risk for your business. The electronics field is very crowded in terms of patents. Many small to medium sized companies in this area may not realise how vulnerable they are. Nowadays, a small company simply implementing a product that conforms to a standard can risk infringing another company's patent(s). A start-up company can inadvertently step on the toes of the "giants" due to a lack of understanding of the patent landscape within which the start-up is operating or is intending to operate. For some, this can end their aspirations to run a successful business. Companies of all sizes should take advice on their freedom to operate in relation to their core product(s) and also on how they can establish their intangible assets - for example, when should they patent their inventions? And how should they go about it? To build a patent portfolio that is worth cross-licensing, there needs to be patents and/or good pending patent applications in it. So what is a "good" patent or patent application? As a patent defines an invention, it is the scope of this definition of the invention that can prevent others from making it. At the very least, a "good" patent should: 1) have a broad definition of the invention; 2) cover obvious work-a-rounds or variants; 3) still be commercially applicable to the business; 4) cover the aspects of the core product that implements the invention. In order to obtain a patent, an invention should be novel (that is, the essence of the invention has not been made available to the public in any form before the filing date of the patent application) and inventive (i.e. not obvious over all mankind's knowledge so far). An invention is obvious if a person skilled in the art (that is, an "unimaginative" expert in the field - this is a fictitious person), whom using their common general knowledge and the documents available to them prior to the filing date of the patent application, i.e. the invention, would have found it obvious to modify or adapt these documents or knowledge to put the invention into effect. Formal IP law can be complex, but to ensure that your particular trade mark, design or invention is properly protected, in all the relevant jurisdictions/markets - organisations sometimes think they are fully protected internationally when in fact they are not - the advice of a specialist intellectual property lawyer or patent attorney can make good business sense. It is important to find a lawyer or patent attorney who is within your budget, has an excellent technical grounding in electronic engineering, computer science, and/or physics, who is not only able to understand a complex technical brief quickly, can draft a specification rapidly, but also is able to engage with engineers and the inventors and draw out alternative embodiments or examples of the invention, and alternative ways of doing something, in order to fully claim the invention. Protecting intangible assets is vital. But that is only part of the process. It is important not just to protect but also to understand the commercial value of the intellectual assets and ensure that you are fully exploiting them, having a clear idea of the commercial goal from the outset. Choice of business model is the key to considering whether value is realised from manufacturing, production, direct sales or licensing. For some companies with the correct experience and know-how it makes sense to manufacture a new product. For others, a license to an established manufacturer/supplier is the best way to get a return from your invention. The correct business model, product proposition and route to market need to be laid out as inputs to an IP strategy ideally from the outset, so that the best form and details of protection can be established. In addition, market issues need to be factored into the process to guide and inform the key IP decision making steps along the way. Some companies - including Coller IP - use sophisticated landscaping tools to help �map' competitors.

Despite the market downturn, new opportunities to trade internationally are still being created and there are real opportunities for companies who can provide products or services that will be taken up by the marketplace and to make money from their intangible assets. However, companies need to ensure that, in taking advantage of these new opportunities, they do not leave themselves open to exploitation, that they understand value of the �hidden treasure' they hold and how to maximise its potential going forward. www.colleripmanagement.com